A Comparison of Hugo Nomination Distribution Statistics

Saturday, January 20, 2024 - 23:22

See also: Part 2, link to the combined Camestos Felapton/Heather Rose Jones analysis.

ETA: Some have requested a copy of my spreadsheet in order to work with the data further. With the caveat that the data hasn't been proofread and the spreadsheet is poorly documented, I've uploaded the folder with the spreadsheet and the graphics used below into Google Docs here. I will not be further modifying or updating the version in Google Docs. I have also corrected some typos below, thanks to the proofreading assistance of readers.

ETA: See some further thoughts at the bottom of the post, marked with the date added.

ETA 2024/01/25: I've added cross-links between the related posts and will continue to update as needed. I'm not used to people actually coming to read my blog! If you like the numbers geekery, consider checking out the rest of my website. I've written some books! I run the Lesbian Historic Motif Project blog and podcast! I natter on about all manner of writing and fannish things!

Regular readers may be aware that my day-job involves pharmaceutical manufacturing failure analysis.This job often involves seeing an anomalous data pattern and then slicing and dicing the data and throwing it into pretty graphs until it starts to make sense. So when I looked at the newly-released 2023 Hugo Award nomination data, my reflexive response on seeing anomalous data patterns was to start slicing and dicing the data and throwing it into pretty graphs to try to make sense of it. (Other people are focusing on questions of why certain nominees were disqualified with no reason given, but large-scale data is what I do, so that's what I'm doing.)

The Observation

The anomaly that caught my attention was the "distribution cliff" in multiple categories, where there was a massive gap between the number of nominations for a small group of items, versus the "long tail" that we normally expect to see for this type of crowd-sourced data. The first question, of course, is whether this is truly anomalous. The second question is what a typical range of distribution patterns looks like. The third question is what the specific nature of the anomaly is. The fourth question is what the root cause of the anomaly is. I won't be able to do more than make a stab at some possible hypotheses for the fourth question.

Methodology

In order to make the data processing more manageable, I decided to focus on only two groups of categories: the length-based fiction categories (novel, novella, novelette, short story, and series) and the fan categories (fanzine, fancast, fan writer, fan artist). My expectation was that these two groups might well demonstrate different behaviors, as well as there potentially being different behaviors within the fiction categories.

Using the nomination statistics provided by each Worldcon, I tabulated the total number of nomination ballots cast for each category and the number of ballots that included each of the top 16 nomination-recipients. (Note: There were not always 16 items listed. Some years reported more than 16 items, but I truncated at 16 for a consistent comparison.) I ignored the question of "disqualifiations" or withdrawals -- the numbers represent what is reported as the raw nomination numbers.

From this, I calculated the percentage of the possible nominations that each of those 16 items received. That is, the number of ballots that listed an item, divided by the total ballots for that category, reported as a percent. This data is displayed as groups of columns, clustered by category. Because the data is reported as a %, the distribution is more easily comparable between categories with different numbers of total nominations.

I selected the following years to analyze:

- 2011 - the earliest year I happen to have data for

- 2012 - the last year before any Sad Puppy activity

- 2015 - the year of the most intense Sad Puppy activity with known nomination slates

- 2017 - the first year of E Pluribus Hugo**

- 2021 - a recent year

- 2022 - a recent year

- 2023 - the current year

**Because I'm looking only at "how many nominating ballots included this item" the difference in how those nominations are processed pre- and post-EPH should not be significant, except to the possible extent that it affects how people nominate.

Note that Fancast and Best Series were added at various times during the scope covered by this study and so are not present in all the graphs.

"Typical" Distribution

I take the data from 2011, 2012, 2017, 2021, and 2022 as potentially representing a "typical" distribution to use for comparison purposes.

2011

2012

2017

2021

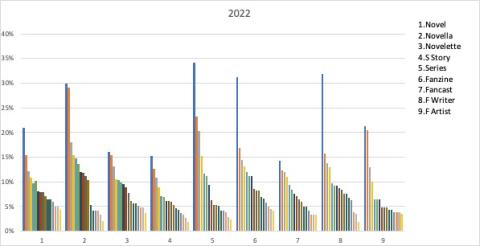

2022

As we see from the above, it's not uncommon for one or two most popular items to extend well above what is otherwise a relatively consistent distribution curve. Although there are significant differences in the number of overall nominations in the different categories (not indicated in these graphs) the distribution by % is remarkably consistent across the categories in any given year. Perhaps more so in the recent years than the earlier ones, when the shorter fiction categories tended to have lower maximum distribution numbers.

If the "initial peak" numbers are excluded, the maximum % of nominations in these categories tends to run in the 10-20% to 10-30% range, with the maximum (including the peak outliers) ranging from 25% to 41%. Overall, let's consider the above to represent the typical distribution we'd expect across years and across categories.

Test Comparison: The Puppy Year

The past year that we might expect to represent the most atypical nomination behavior is 2015: the year most significantly impacted by slate nominations associated with Sad Puppy (and adjacent) nominators.

2015

We do see a difference in that--rather than the occasional one or two initial "peak" nomination percentages in a category, some categories have several items with significantly higher percentages than the bulk of the distribution curve. But although the initial slope of the distribution curve may be steeper, it's still identifiably a curve. And the range of results is solidly in line with the group we're considering "typical", i.e., with peak percentages ranging from 15-36%. Overall, the data does look consistent with a subset of nominees being "pumped up" above the expected shape of the distribution, but it doesn't seriously distort the overall picture.

The 2023 Anomaly

Now let's look at the 2023 distributions.

2023

Having previously answered question #2 (what does a typical range of distribution patterns look like?) we can now move on to question #1 (is the 2023 distribution anomalous?) and the answer is clearly "yes." In terms of the shape of the distribution curve, novelette, short story, fan writer, and possibly fancast look more or less like our "typical" pattern, even allowing for the initial "peak" outliers in novelette and short story. But novel, novella, series, fanzine, and fan artist all have a large group of highly similar % nominations, followed by a sharp drop to the "tail" with lower percentages. (This is what I'm calling the "distribution cliff.") The gap in each category falls between:

- Novel: 47% to 9%

- Novella: 44% to 11%

- Series: 58% to 4%

- Fanzine: 33% to 8%

- Fan Artist: 25% to 10%

Furthermore, the maximum % of nominations across the board is double what we've seen in the "typical" distributions: 30-66%. So we have two obvious anomalies: the "distribution cliff" and the most frequently nominated items appearing on twice the proportion of ballots relative to any other year studied.

What's Going On?

Now we've answered questions 1-3. We've seen what the range of "typical" distributions are, even in a year with known manipulation of the nomination numbers. We've seen that 2023 distributions are clearly anomalous. And we've identified at least two measurable features of that anomaly. Now we come to question #4: What's the underlying cause of this pattern?

The best I can do is suggest some hypotheses and poke at possible support or contradictions for them. In no particular order...

Hypothesis 1: Large numbers of nominating ballots drew from a small "slate" of prospective choices, resulting in both the high percentages for the top nominees and the sharp drop to the remaining members. Pro: the "distribution cliff" does look somewhat similar to the slating dynamic in 2015, but in much more exaggerated form. Con: In several categories, the cluster of very high % nominations is larger than the number of nominees per ballot, and it would take massive coordination to create this tighly-clustered effect across the number of ballots involved for the fiction categories.

Hypothesis 2 (hat tip to JJ): The "distribution cliff" represents a significant range of nominees that have simply been omitted from the published statistics, leaving only a group of the highest nomination recipients and a set with relatively low nomination numbers. Pro: The data to the right of the "cliff" look like a typical "long tail" distribution. This hypothesis would be consistent with the omission of fiction titles that we might well expect to see in the long list, given the specific titles that are present in the high-percent group. (In some years, the statistics include the total number of different items nominated in each category. This would be useful data for evaluating hypothesis 2, but is not available for 2023.) Con: The math doesn't add up for there to be a chunk of missing "mid-range" nominees. For this, let's introduce another anomaly.

% of Available Nominations Accounted for by the Long List

For this, I calculated the number of "hypothetical available nomination slots" by multiplying the number of nomination ballots for each category by 5. Then I added up the number of nomination slots accounted for by the long list (as presented). The slots accounted for are presented as a percentage for each category. Note that in most categories, the proportion of available slots accounted for by the Long List data is about twice the typical proportion. It's typical for people not to use up all their available nomination slots in every category, so this data suggests that many more people use up all or a majority of their avilable slots (and--as we've seen above--used them to nominate from a relatively small selection of options).

When you look at 2023 categories like Novel and Series, there simply isn't room in the numbers for a substantial number of "missing mid-range nominees" from a normal distribution curve. That leads us to...

Hypothesis #3: The math is bogus. That is, the reported nomination statistics include large numbers of nominations attributed to the "top group" that do not arise from an actual nomination process. Two possible methods (related to hypotheses 1 & 2) could be at play. Either a fixed number of false nominations (proportional to the overall true nominations in the category) have been added to a variable number of the top picks, or the actual nomination numbers from a "missing mid-range" have been added to the items that are reported as the top picks. A third possible sub-hypothesis here is that there was a massive programming error in the software that was processing the nomination data that moved nomination counts around. I'm not going to do pros and cons on this one because I've introduced too many variables.

Conclusions

Well, there really aren't any conclusions other than the ones that were immediately apparent from the raw data. The 2023 Hugo Nomination Statistics are implausible and anomalous and as a result we don't actually know who should be on the Hugo Long List. (And--based on factors that I haven't discussed here--we don't entirely know who should have been on the Hugo Short List.)

ETA 2024-01-22

I had some further thoughts on timing and the reasons given for timing of the nomination stats. This was originally posted on Bluesky, and then expanded slightly as a comment on File770.

One quoted phrase [in an article at https://mrphilipslibrary.wordpress.com/2024/01/21/hugo-nominating-stats-rascality-and-a-brief-history-of-where-it-all-started/] got me thinking more deeply about something. One reason for the delay in releasing the nomination stats was quoted as “this delay is purely to make sure that everything I put out is verified as correct (and the detailed stats take time to verify, there’s lot of stuff going on there.” [McCarty]

But remember that unexpected delay when announcing the finalists, way back earlier? Surely that was the point when everything needed to be verified as correct? Like: making sure titles and names were correct and consistent so that nominations were tabulated and processed correctly? And an extensive verification process before the nominations were tabulated to generate the finalist list makes sense and is understandable. And that was what we all told ourselves at the time and tried to be patient because of it. But the Long List is not a separate entity from the Short List. It’s just a peek at a larger part of the same list.

That’s why the nomination stats are usually able to be released immediately after the award ceremony: the work should have been complete months before. The nomination stats document should be ready to release at the time the finalists are announced. [Note: "should be" in the sense that all the data is fixed and known at that point. But obviously the question of whether the people authorized to know that data and the people preparing the voting/nomination stats for release are the same people has an impact.] So what possible verification and correction could still be pending after the date of the announcement of the finalists? Much less after voting is complete? Much less for three months after the awards are given out? It doesn’t make sense.

Any errors or inconsistencies whose correction contributed to the 3 month delay after the con would be errors and inconsistencies that existed at the time the nomination data was processed to generate the finalist list.

Therefore, even if it were true that the long delay in getting the nomination stats out (not just 3 months, but 3 months plus the time between release of the finalist list and the time of the convention) were due to the need to correct errors and inconsistencies, that in and of itself indicates that the data generating the finalist list was deeply flawed.

On the other hand, I could propose a “hypothesis #4” to add to the ones above: The finalists were a semi-arbitrary selection–perhaps based on actual nomination data, but not determined by the prescribed nomination process–and the long delay was due to the need to create long-list data that supported the published finalist list. (Note that none of my hypotheses are intended to be taken as being solidly supported or being what I believe, they are simply models that could be consistent with the observed data.)

Major category: