Blog

Monday, November 20, 2017 - 11:00

This is a very theory-intensive book -- historiography rather than history, and not well suited for the casual reader. But there are some great discussions that made it worth tackling. The writing is very dense and my summary only touches on the outlines of the discussion rather than its specifics. Although theories about how we study and interpret history might seem rather removed from the process of writing lesbian historical fiction, from another angle, the two fields have a great deal of overlap. Consider the question of whether our approach to history is focused on finding identity with our own specific experiences and relationships, or whether we are seeking to understand and appreciate people whose lives have connections with ours but also wide areas of difference. Do we seek to find/write "lesbians in history" from a very narrow definition of the word "lesbian" or do we seek to find/write themes of women's same-sex relationships expressed in a multitude of ways? Do we consider sexual activity to be a necessary defining aspect of those persons we study/write under the rubric of "lesbian" or is it only one of a cluster of important themes? Historical fiction (not just lesbian historical fiction but the entire field) has a pervasive uneasiness around how closely similar historical figures need to be made to modern mindsets in order to be sympathetic to modern readers. In the specific case of lesbian historical fiction, this concern can work to delegitimize the very concept of lesbians in history, just as some historical theories work to erase lesbians as a topic of valid study. And that's why I love finding the parallels in books like this to my own thought processes around the project of writing.

Major category:

LHMPFull citation:

Traub, Valerie. 2016. Thinking Sex with the Early Moderns. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812223897

Publication summary:

Theoretical considerations of studying sexuality in the early modern period.

[The following is duplicated from the associated blog. I'm trying to standardize the organization of associated content.]

This is a very theory-intensive book -- historiography rather than history, and not well suited for the casual reader. But there are some great discussions that made it worth tackling. The writing is very dense and my summary only touches on the outlines of the discussion rather than its specifics. Although theories about how we study and interpret history might seem rather removed from the process of writing lesbian historical fiction, from another angle, the two fields have a great deal of overlap. Consider the question of whether our approach to history is focused on finding identity with our own specific experiences and relationships, or whether we are seeking to understand and appreciate people whose lives have connections with ours but also wide areas of difference. Do we seek to find/write "lesbians in history" from a very narrow definition of the word "lesbian" or do we seek to find/write themes of women's same-sex relationships expressed in a multitude of ways? Do we consider sexual activity to be a necessary defining aspect of those persons we study/write under the rubric of "lesbian" or is it only one of a cluster of important themes? Historical fiction (not just lesbian historical fiction but the entire field) has a pervasive uneasiness around how closely similar historical figures need to be made to modern mindsets in order to be sympathetic to modern readers. In the specific case of lesbian historical fiction, this concern can work to delegitimize the very concept of lesbians in history, just as some historical theories work to erase lesbians as a topic of valid study. And that's why I love finding the parallels in books like this to my own thought processes around the project of writing.

# # #

Chapter 1 - Thinking Sex: Knowledge, Opacity, History

This book is historiography rather than history, that is, it takes a strongly theory-intensive look at the ways in which sex and sexuality are studied and raises questions about the current process of doing history around the topic of sex. Sexuality is used as a lens to examine how people in history (and today) think. In particular, it’s concerned with the concept of knowledge and what it means for a person to “know” something sexual, whether as an individual in history or as a historian studying the topic. Different approaches to the identification and understanding of knowing make sex a difficult topic to study as well as a site of conflict.

One example of these approaches is the question of how we divide the world between passionate friendship and eroticism. When is a kiss (or an embrace, or the sharing of a bed) just a kiss and when is it erotic? The book has a strong focus on women’s experience and the ways it has been excluded from study. Because of this, Traub is very inclusive of female same-sex experience, and often focuses specifically on the ways in which female same-sex eroticism has been excluded or erased from larger theoretical movements in historical study.

Chapter 2 - Friendship’s Loss: Alan Bray’s Making of History

This chapter examines how historians have understood the interface between friendship and eroticism, focused through the lens of Alan Bray’s study of friendship and homosexuality among men in Renaissance England. He’s concerned with the contradictory position of intimate relations between men in the Renaissance which treated friendship and sodomy as clear contrasts, despite massive overlap in practice.

Although the chapter is mostly concerned with male relations, it also touches on the phenomenon of marriage between women. Traub emphasizes the different social receptions of the ideal of male versus female homoerotic relationships. One historiographical problem is that of researchers who impose moral judgments on asexual versus sexual friendships. There is a brief consideration of the intersection of documented cases of erotic desire with rituals associated with sworn friendship, as we find in the diaries of Anne Lister. Also noted are friendship rituals that partake of the forms of marriage, such as the co-burial of Ann Chitting and Mary Barber.

Chapter 3 - The New Unhistoricism in Queer Studies

This chapter examines historicism and teleology, that is, the question of whether history “moves” in a meaningful direction. Do historical phenomena have systematicity and coherence or are they discontinuous? In particular, is there a connected “history of homosexuality” across the ages? What are the hazards of studying sexuality from a point of view that assumes a present enlightened truth.

Chapter 4 - The Present Future of Lesbian Historiography

Traub critiques the usefulness of an assumption of a “sameness/difference” polarity in framing women’s same-sex relationships. She notes previous major works that take a “continuist” approach to history (i.e., looking for a single continuous narrative of lesbianism) including Faderman, Castle, and Brooten. These historians are critical of Foucault’s periodization model that splits the history of sexuality into a focus on “acts” versus a focus on “identity”. Traub notes the conceptual simlarity across time of lesbian concepts, e.g., female intimate friendship as examined by Vicinus and others. She urges that the “present future of lesbian history” should look at these recurring patterns across time. Thus circumstances and behaviors in other times may look like the modern definition of “lesbian” because they emerge from similar sets of continuing preoccupations about women’s bodies and behaviors. She considers studies of various historic types of representations or relationships that contributed to or have been retroactively connected with the modern lesbian. She presents a recapitulation of various images and interpretations of female same-sex relations from the 17th century to today and then draws up a list of themes relevant to these recurring patterns. (A very long list, or I would include it here.)

Chapter 5 - The Joys of Martha Joyless: Queer Pedagogy and the (Early Modern) Production of Sexual Knowledge

This chapter looks at sexual knowledge and ignorance, riffing off an example of dialogue in the 1638 play “The Antipodes” by Richard Brome, in which a still-virgin wife of three years is speculating on heterosexual knowledge (complaining to a friend about not knowing how to get her husband to perform), while recalling a same-sex erotic encounter. The woman’s request for her female friend to instruct her about sex is portrayed as naïveté. In contexts like this, there is no concept that a male versus female sexual partner indicates a particular orientation or identity, although “spouse” versus “non-spouse” is a relevant category. Similarly there is no hint in this dialogue of a concept of “the closet” or an expectation of negative reactions from others to her relation of the same-sex encounter. The only aspect of the scenario that is considered problematic is her husband’s sexual indifference.

The chapter then considers various other examples of sexual dysfunction in drama, and how the situations are addressed by non-marital sexual activity, regardless of gender. What do we, as moderns, “know” about early modern sex and how do we know it? Among the motifs available from literature are the older woman who sexually initiates a younger one--a cross-over motif from pornography. These texts question the “natural, innate” nature of sexual knowledge. Rather, it is a type of cultural knowledge and practice.

Chapter 6 - Sex in the Interdisciplines

Traub examines the overlapping contexts of history, literary criticism, and queer theory for studying the history of sexuality. There is an extensive description of the state of the field as the author experiences it. This includes a comprehensive catalog of the understanding of English sexual culture in 1550-1680 and a discussion of sexual vocabulary in use by 1650.

Chapter 7 - Talking Sex

This chapter examines descriptive, metaphoric, and humorous language around sex. How were people represented in historic records and literature as speaking of erotic and sexual acts? What language was used for sex workers? And what shades of meaning did the various terms carry? There is an extensive catalog of sexual vocabulary (which would be extremely useful to a writer setting bawdy scenes in this era). In the discussion of sexual humor, Traub discusses how to edit, translate, and annotate texts containing early modern sexual language in order to convey all the layers and nuances of meaning it held. There is a special discussion of language around dildos.

Chapter 8 - Shakespeare’s Sex

This chapter looks at interpretations of Shakespeare’s personal sexuality as embodied in his sonnets (as opposed to the sexual themes in his plays or the evidence of his biography). The study is less concerned with Shakespeare’s actual life than the shifting “knowledge” of that life. That is, how people have come to conclude the things they think they know about him.

Chapter 9 - The Sign of the Lesbian

Traub addresses the question, “Why do we need a history of lesbianism?” That is, why would we need one that focuses on “lesbian” as a specific and defined field of study, as contrasted with the need or usefulness of lesbian history to lesbians in particular. Traub notes a conjunction of “queer history” doubts about history itself along with disinterest in lesbian identity in the context of queer studies. This seems to require identifying a general benefit from the field if a continued interest in “lesbian history” is to survive. To this end, she suggests destabilizing the meanings of both “lesbian” and “history” to ask, “What does it mean to identify ‘lesbian’ in the context of ‘history’?” Why and how does the concept of “the lesbian” become pivotal in history?

Traub’s answer begins, “My purpose is to supplement these revisionist accounts of queer theory by suggesting that it is precisely the history of lesbianism, when reconceived as a problem of representation and epistemology, that offers a valuable heuristic for crafting an analysis that is simultaneously feminist and queer. Reasoning that one impediment to recognizing these interventions as queer theory is that many of these innovations have been produced by means of analysis that is explicitly historical, I argue that ‘the lesbian’ presents not only a limit case for queer theory, but a methodological release point for anyone interested in sexual knowledge--past, present, and future.”

Traub discusses different approaches and concerns of lesbian and gay historical studies versus queer studies. The field currently privileges the queer studies approach. She looks at works in which the figure of “the lesbian” is foregrounded but is concerned that they dismiss the contributions of historicity. Must history be discarded to include the lesbian in queer theory? The lack of interest in lesbian history outside the field producing it means that it rarely influences the construction and debate of larger theories. There is a conflict between the tendency to see lesbian history as rooted in identity, with queer theory associated with post-identitarianism.

Traub suggests that dismissal of the lesbian from theoretical consideration on the basis of rejecting identitarianism assumes the narrowly modern identity associated with the label, and ignores the varied and discontinuous histories of lesbianism. That is, queer theory narrows lesbian identity to a concept easy to dismiss and to consider historically irrelevant. If “the lesbian” can be confined to a 20th century identity, then all pre- and early modern evidence of female homoeroticism becomes “not queer enough” to contribute to queer theory.

The denigration and marginalization of lesbian studies, even by some of those engaged in it, comes from multiple sources: the marginalization of sexuality studies, the tendency of those engaged in lesbian studies to have a broader focus to their work, and shifting popular attitudes that consider the label “lesbian” as retrograde and associated with the white middle class. There is a false belief that the recency of the label “lesbian” represents a lack of a historic subject for study. This attitude persists in the face of awareness of the term’s long history.

A more historic approach would be to examine women’s understandings of their own experience, rather than viewing lesbian history as a “search and rescue” project. Traub notes the valuable data in Anne Lister’s self-examinations and self-reporting of her sexuality. Traub draws attention to how, of all “queer” identity labels and categories, only “lesbian” seems to be deemed retro and essentializing--in the face of no logical difference from similar uses of “gay” or “trans”. She suggests (without quite using that term) that systemic misogyny can’t be ruled out as an explanation for the marginalization of lesbian history within queer studies.

Chapter 10 - Sex Ed: or, Teach Me Tonight

This chapter focuses on the process of learning, especially with regard to sexual knowledge. Literary examples are given of a character learning or teaching sexual techniques. Sexual knowledge in particular is often communicated in allusions and slang, or in meaningful omissions. The chapter mostly contains discussions of theory and modern pedagogy and provides a summary of the book’s main points.

Place:

Event / person:

View comments (0)

Sunday, November 19, 2017 - 07:00

I bought Barbary Station by R.E. Stearns based on the response of various advance reviewers that boiled down to “lesbian space pirates; what more could you want?” Well, evidently I want more. Barbary Station appears to be a competently written space opera involving pirates, malevolent AIs, and bionically-enhanced cyber-hacking engineers. The central protagonists are a same-sex couple in a pre-existing and utterly taken for granted relationship. But having gotten four chapters in, I have yet to find myself caring what happens to them or whether they succeed. The story simply hasn’t grabbed me. Space opera isn’t one of my top ten genres, but there have been many books in that general subgenre that I’ve loved, when the characters caught my interest. So I’m going to have to leave this one at Did Not Finish and forgo a rating. If you generally enjoy space pirates and plots that revolve around engineering problem-solving, you may well have a very different experience.

Major category:

ReviewsSaturday, November 18, 2017 - 10:15

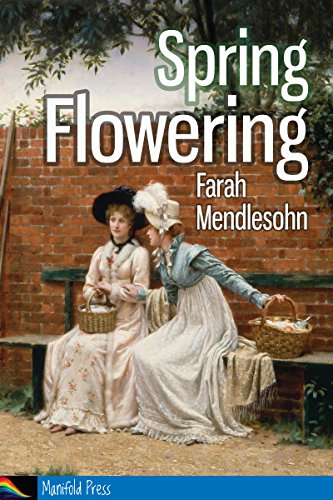

Lesbian Historic Motif Podcast - Episode 28 (previously 16c) - Book Appreciation with Farah Mendlesohn

(Originally aired 2017/11/18 - listen here)

Farah talks about two novels by Ellen Galford that she really enjoys for their historic elements. (And incidentally inspired me to add Moll Cutpurse to the topic list for the podcast.)

* * *

(Transcript commissioned from Jen Zink @Loopdilou who is available for professional podcast transcription work. I am working on adding transcripts of the existing interview shows.)

Heather Rose Jones: Farah Mendlesohn, author of the Regency era romance, Spring Flowering, is joining us again this week to talk about some of her favorite historic novels featuring lesbians or bisexual women. Welcome, Farah!

Farah Mendlesohn: Hello!

H: Tell me about some of your favorite historic stories.

F: Okay, so the one I picked is one of my favorites; it’s Ellen Galford’s Moll Cutpurse.

H: Oh, yeah.

F: Which, I don’t know how many people will have read it because it’s not in print anymore as far as I know. Although, I think it might be available in ebook. It’s set in 17th century London and I’ve already mentioned [see: episode 16b] that the 17th century is an absolute passion of mine. It’s actually the Restoration period and Moll Cutpurse is actually a character originally devised by Daniel Defoe, who I think is so much more interesting than most people realize. [Correction: Daniel Defoe’s character was Moll Flanders, who was entirely fictional.] He was a social satirist. A lot of his stuff is taught straight when actually it’s more like Dickens, it’s coruscating criticism of society. But he has this character, Moll Cutpurse, who is a thief, a runner of thieves, a general bad girl who dresses in men’s clothing and smokes a pipe.

Ellen Galford, who’s a feminist writer who did most of her writing in the late 80s, wrote this lovely take on her, in which she’s essentially a very butch lesbian, very sweet, shy sixteen year-old who is terribly jealous of a man who seduces the girl she loves until she meets the apothecaries daughter who says, ‘Actually, I much prefer women and let me show you what having a woman’s body can be like.’

What I loved about it was it’s not a coming out story in the conventional sense, there is none of this discussing, ‘Oh, we are this separate thing.’ It’s much more… this is something that women do, and some women only do it and some women do things with men too, but here is how we can enjoy ourselves. And that, within the thieves’ society, they set up a relationship that everybody around them respects and just kind of takes for granted. In terms of the 17th century and the Restoration era, to start with there is a man shortage. I don’t know if most people realize this, but the death rate of men in the English Civil War is higher than in the first World War. It’s something like one man in every ten is dead.

H: Wow.

F: Okay, there’s lots of surplus women. Pepys talks in his diary about desperately trying to find a husband for his sister, dowries are shooting up, but one of the things Defoe talks about in Moll Flanders, that’s a book that’s often described as a romp, but it’s actually about the sexual exploitation of a young girl in a period when men can have their pick and do. [Note: this is accurate for Moll Flanders but not for Moll Cutpurse.] The king, of course, is setting the tone. That’s often written about as if that’s nice and jolly. I find it fascinating, Victorian writers don’t approve, but writers of the 60s often do. Actually, it’s a nasty exploitative period and one of the things Galford manages to do is to show how the relationship between the two women helps protect them from that. That it actually gives them family, community, people to be with.

It’s just lovely and I love the fact that it’s not explicit in the pornographic sense, but there’s a scene in it when Moll’s lover, whose name I can’t remember, I’m afraid, is touching her breasts and lifts her breasts in a way that struck me as a very female on female thing to do. That sense of feeling breasts as kind of part of somebody, rather than just admiring them, looking at them in the way that you find in a lot of heterosexual romances. The only way I can describe it is, you can feel the weight of Moll’s breasts in her hand and that sense of weight of them is… I don’t know, whenever I read lesbian erotica that’s one of the things I always see that I don’t see in heterosexual erotica and romance, if that makes sense. That physicality of the female body.

I just love the book. Oh, and it ends with the traditional scene of Moll Cutpurse in the pillory and she has to give this speech and she turns it into what we would now think of as almost rap music. Because in the 17th century we start seeing the convention of the confession speech.

H: Yes.

F: It’s a genre in itself, it really is. There’s lovely book called The Victorian Invention of Murder that talks about this. In this book, Moll Cutpurse uses that talk about herself to frame herself, to narrate herself in what we would now think of as quite a post-modern way but is actually more common to the 17th century than it is to the 19th.

H: Yeah, and another thing I love about stories about Moll Cutpurse is that the historic figure, to the extent that we have information on her, was just as wonderfully outrageous.

F: Oh, she was clearly a character. One of the other things about the 17th century, of course, is that the second half, from the Civil War onwards, is the period of News scenes, it’s when newspapers are growing up. They start to create what we would now call celebrity culture.

H: Yeah.

F: They wanted to write about the likes of Moll and the likes of Moll realized that they could use the newspapers. They can use these journals and you can see that lovely give and take. She’s not a victim, she creates herself and Ellen Galford really puts that over.

H: Yeah, and there’s, not just in England, but in the 17th century there’s Spanish examples where using the cultural celebrity was a way of protecting yourself if you were a gender outlaw.

F: Absolutely, you become bigger than life. You become somebody that they can’t touch because the stories are so wild, they cannot possibly be true and that’s a very good way to hide reality.

H: I think you mentioned that there was another of Ellen Galford’s books that you really enjoyed.

F: Yes, when you first suggested this to me, I didn’t quite realize you wanted historical novels. I thought we’d just on the romance and I adore Fires of Bride, which does have a historic element. So that’s about an artist who paints these amazing pictures of saints for her first exhibit and then loses all kinds of impetus and takes up an offer of a female Scottish doctor to go and reside in this woman’s castle… It’s all terribly gothic, where they have a torrid romance for the winter and then get bored of each other. The doctor moves her into an area on the island where she starts creating artwork from bits of scrap metal. Then they discover the old abbey that was they’re in the early-medieval period, the kind of last outpost of Christianity before it’s nothing but dragons and sea monsters, and they discover the buried skeleton, or the abandoned skeleton, of a young woman and get flashbacks into the Viking raid that destroyed the convent.

H: Yeah, I thought I remembered the historic part.

F: Yeah, and there’s romance in there and a real sense of women as a community. The things that really come through in that book is women acting for each other. At one point the local tourist factory essentially gets taken over by a women’s co-op to turn out political Scottish tea towels, talk about witch burnings, and throwing stools at priests. Although there are men in the book, the entire book is very woman-centered. The men kind of drift to the background right the way through. There are several torrid romances and there is also love. What I loved about that book is that they’re not the same thing and I found that really interesting because I’m very much somebody who decided in her life that torrid romance and love and actually getting on with my life didn’t necessarily go together. I quite like a quiet life, thank you very much. This book very much tackles the different ways of loving, the different ways of being in love, in ways that are just fantastic. Again, it’s very earthy, it’s very physical. I think I’m very attracted to writing that gets the physicality of women. A book that I love, but never quite fell in love with, was Tipping the Velvet.

H: Uh huh.

F: I don’t think I ever quite fell in love with Tipping the Velvet because it’s almost too unphysical for me. I know there’s descriptions of sex in there, but what there isn’t, is that sense of the scent and feel of a woman. There isn’t that visceral-ness. What I look for in romantic writing is that connection to the visceral. We’re not talking erotica here, just that sense of the other person’s physical being that I think Ellen Galford gets beautifully.

H: Well, thank you so much for sharing some of your favorite books with us. All the books that were discussed here will be linked in the show notes for people to follow-up on them, and thank you again, Farah, for joining us on the Lesbian Historic Motif Podcast.

F: Thank you.

Show Notes

In the Book Appreciation segments, our featured authors (or your host) will talk about one or more favorite books with queer female characters in a historic setting.

In this episode Farah Mendlesohn recommends some favorite queer historical novels:

Links to the Lesbian Historic Motif Project Online

- Website: http://alpennia.com/lhmp

- Blog: http://alpennia.com/blog

- RSS: http://alpennia.com/blog/feed/

- Twitter: @LesbianMotif

- Discord: Contact Heather for an invitation to the Alpennia/LHMP Discord server

- The Lesbian Historic Motif Project Patreon

Links to Heather Online

- Website: http://alpennia.com

- Email: Heather Rose Jones

- Twitter: @heatherosejones

- Facebook: Heather Rose Jones (author page)

Links to Farah Mendlesohn Online

- Website: Farah Mendlesohn

- Twitter: @effjayem

Major category:

LHMPFriday, November 17, 2017 - 06:00

This is a short piece within de Bodard’s “Dominion of the Fallen” world, falling hard on the heels of The House of Shattered Wings and I believe introducing us to a key character who will feature in The House of Binding Thorns. It goes beyond character study, giving us a tightly packaged perilous adventure (perilous from several directions) featuring not only the harsh cut-throat politics of the various Fallen houses, but the lingering hazards of the magical cataclysm that destroyed Paris--hazards that have no respect for house loyalty. It probably isn’t a story that would stand alone for someone who hasn’t read at least one of the novels--there’s far too much essential world-building to be able to summarize for a piece of short fiction. But it’s exactly right for a short bonus feature for those who are following the series.

Major category:

ReviewsTuesday, November 14, 2017 - 09:55

Last week I talked about how manipulation of point-of-view can change the entire flavor of what I’m writing. This week, rather than talking about my own writing, I’d like to bring together three things that have passed through my brain recently about understanding and portraying romantic relationships between women in historical settings.

The one that really sparked this train of thought is a podcast titled Frankentastic being created by Tansy Rayner Roberts and put out by Twelfth Planet Press in fulfillment of a stretch goal for the kickstarter for the forthcoming anthology Mother of Invention. The premise of Frankentastic is a fairly straightforward re-gendering of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein read as a serial. All the male characters (which is the vast majority of the on-page characters) become female, while the female characters are converted either to male or non-binary characters. Other than names, pronouns, and gendered references (like mother/father/parent), the text remains completely as the original. But what seems like a simple little conceit makes some interesting differences in how the characters in their relationships read.

The biggest thing that struck me was how overwhelmingly homoerotic the language of the story is: not merely in the context of Victor(ia) Frankenstein and friends, but also in the context of the initial framing story of Robert(a) Walton’s sea voyage and the interactions with associates and crew. The language these characters use is effusively and overwhelmingly romantic and even sensual with regard to same-gender friends and associates. I don’t know whether it is striking me more in this audio version than it did back when I read the book due to the immediacy of the medium, or whether I notice it more when those exchanging the sentiments are women for personal reasons, or whether I’m more likely to discount such effusive sentiments as literary convention when spoken between men, or some other reason. But the take-away observation here is that an early 19th century writer, of good birth if unconventional lifestyle, considered it normal, natural, and unremarkable to put expressions of same-sex devotion and love in the mouth of her characters that—if written today—would be interpreted unambiguously as expressing homosexual desire.

And although Shelley’s work placed this language in the mouths of male characters, I know from the research I’ve studied for the Lesbian Historic Motif Project that similar language was considered normal, natural, and unremarkable between actual women in everyday life. We know this from correspondence and diaries and reported conversations, as well as from the depictions of emotionally intense female friendships in literature of the time. It’s one thing to read books are articles discussing this phenomenon, but somehow it’s a viscerally different matter to listen to it being expressed in audio, and particularly in a context where gender-swapping has highlighted the import of the conventions.

So, there’s that.

The second stream feeding into these thoughts is having just read Farah Mendlesohn’s Spring Flowering (set in the same era) and seeing how noticeable the contrast is between how her characters express and enact the spectrum of same-sex emotional (and sensual) relationships, reflecting the same conventions we seen in Frankenstein, as compared to the depiction of historic characters more commonly found in lesbian historical fiction that attributes a very modern-feeling guilty self-consciousness around experiencing and expressing same-sex romantic desire. The characters in Frankenstein feel no need to reassure themselves or their companions of the purely platonic “no-homo” nature of their relationship, just as their real life sisters felt no embarrassment or guilt at the most effusive expression of emotional bonds with each other. Because that was how close friends were expected to act with each other.

Now, you may protest that close friends may have felt free and unselfconscious to act in that way precisely because there was no actual erotic component to their relationship. But we know that isn’t the key, because we know that some early 19th century persons who wrapped the enactment of their romantic friendship in this effusive passionate language and behavior also had erotic relationships. Not all of them. Perhaps not even most of them. But some of them. And we know—from our admittedly scanty scraps of direct evidence—that they did not consider their feelings to be a separate species of relationship from non-erotic romantic friendship. And I must acknowledge that the differences between male and female sexuality may make the two experiences diverge somewhat on this point. But the point is that you can write an early 19th century story in which two women proclaim their love for each other publicly, express themselves in the most passionate terms in correspondence, writing of the desire for kisses and embraces and the longing to sleep together and the dream of sharing their lives together, have these desires and expressions be known to all their associates, and have them be free of both internal and external condemnation and suspicion for those expressions. (Which isn’t to say that there weren’t occasions when women’s passionate friendships did rouse suspicion and censure, but only that it was a far from universal consequence.)

The third stream of thought on this comes from editing an author interview for my podcast where the author is talking about honoring how brave and daring and ground-breaking woman-loving-women in history were. And this is where I long to immerse people more in the historical context—the ways that actual women in history expressed and enacted their same-sex relationships. Because they weren’t all lonely, daring radicals—not necessarily and not generally. Not until the 20th century, that is. For the most part, they were finding ways to express their love and desire for each other in ordinary and conventional ways that their society considered not merely acceptable but, in many cases, praiseworthy. To be sure, the ways they found generally did not involve making public proclamations of the sexual nature of their relationships, or of political agitation for legal equality (hard to do when women as a class did not have legal equality!). But the depiction of pre-20th century women who loved women as having the same sort of tormented and conflicted internal life that we see depicted for early 20th century women is simply flat-out historically inaccurate. And I’d love to see more historical fiction that reflected that. Perhaps what we need is more familiarity with literature of the times that depicts intense same-sex emotional relationships—and if we can’t find them with women, then gender-flip the men and enjoy the ride!

Major category:

ThinkingMonday, November 13, 2017 - 07:00

One of the contradictory features of reasoning about same-sex relationships in the past is the circular logic that same-sex romantic relationships could not have been socially approved, therefore evidence showing social approval for conjunctions of two people of the same sex must not represent romantic relationships. And while the careful historian avoids making claims beyond the known evidence, the imagination is sparked by examples such as this one where two women are given a commemoration after death--a commemoration that was within the control, and therefore with the approval of, their families--that represents them with the forms and symbolism normally attributed to married heterosexual couples.

Major category:

LHMPFull citation:

Bennett, Judith. 2008. “Two Women and their Monumental Brass, c. 1480” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association vol. 161:163-184.

Publication summary:

An examination of a joint memorial brass for two women.

[The following is duplicated from the associated blog. I'm trying to standardize the organization of associated content.]

One of the contradictory features of reasoning about same-sex relationships in the past is the circular logic that same-sex romantic relationships could not have been socially approved, therefore evidence showing social approval for conjunctions of two people of the same sex must not represent romantic relationships. And while the careful historian avoids making claims beyond the known evidence, the imagination is sparked by examples such as this one where two women are given a commemoration after death--a commemoration that was within the control, and therefore with the approval of, their families--that represents them with the forms and symbolism normally attributed to married heterosexual couples.

# # #

The parish church in Etchingham (East Sussex) has a memorial brass jointly commemorating two never-married women: Elizabeth Etchingham who died in 1452, and Agnes Oxenbridge who died in 1480. This article considers both the specific life circumstances of these two women and the general context of funeral monuments dedicated to same-sex pairs.

As might be guessed, the church in Etchingham was built by, and served as a resting place for, the Etchinghams and might in some senses be considered a family church. When designed in the late 14th century, the chancel was created to serve as a family mausoleum for generations of Ethchinghams to come, and most of the funeral brasses commemorate the principle heirs of the dynasty. But in 1480 a brass was laid in the church commemorating someone who was not only not a male heir, but an unmarried daughter: Elizabeth Etchingham. Her exact relationship to the main line (and consequently her exact age) are not conclusively determined. But it is clear that she had some significant relationship to the woman she shares the memorial with: Agnes Oxenbridge, a daughter of another prominent east Sussex family.

Bennett notes Alan Bray’s exploration of the social place of intense same-sex friendships in European society (The Friend) and the evidence that the Christian church has accommodated and celebrated those friendships both in life and in death. Examples are given of the joint tomb from 1391 of the English knights William Neville and John Clanvowe in Galata near Istanbul, which depicts their coats of arms displayed impaled in the style normally used for married couples. Most of Bray’s examples are more modern (from the 17th through 19th centuries) and (virtually?) all were male. Bray emphasized that these monuments celebrated emotional intimacy and friendship and cannot be taken as proof of sexual relationships, but they do establish a genre of memorials that treat same-sex couples with the symbolism and dignity similar to that given to married couples.

The Etchingham-Oxenbridge brass survives in complete form and is clearly readable. It shows two women with their hands raised in prayer, turned in semi-profile toward each other. Elizabeth Etchingham is depicted as a smaller figure on the left, with the loose flowing hair down to her hips, a motif associated with a young unmarried woman. Agnes Oxenbridge, on the right, is depicted larger, and her hair is pinned up but not covered, again indicating an unmarried state but not indicating youth. Both wear narrow bands about their hair decorated with a triangular ornament, and they wear identical fashionable gowns.

The text appears in two columns separated by a vertical line, clearly associating each of the two passages with a specific figure. On the left, for Elizabeth, the text identifies her as the first-born daughter of Thomas and Margaret Etchingham, died December 3, 1452. For Agnes, the text identifies her as the daughter of Robert Oxenbridge and gives her death date as August 4, 1480, concluding with her request for God’s mercy on both women. While this sort of separated text was not unknown from other memorials, the more usual format for married couples is a single joint text. The lack of any mention of husbands in either woman’s entry is very strong presumptive evidence that they never married, especially in combination with the depicted hairstyles which mark them as unmarried.

Their exact position within the Etchingham and Oxenbridge families is difficult to pin down, as neither is mentioned clearly in family genealogies (which focus more on the lines with descendents), and due to the tendency not only for names to repeat within a family, but in some cases for multiple children to be given the same first name. (As children were typically named after a godparent, there wasn’t always a choice of a unique name available, given the socio-political constraints on godparent choice.) But after much analysis, Bennett concludes that most likely Agnes Oxenbridge was the daughter of the second Robert Oxenbridge listed in the genealogies, and thus was born around 1425. This means that she would have been in her twenties when Elizabeth Etchingham died and in her fifties when she herself died. Elizabeth Etchingham’s exact position is less certain: depending on which generation she was born into, she herself might have been in her twenties when she died (and thus of an age with Agnes) or might have been a child at her death.

Their unmarried status was unusual for the time--less than 10% of women of their social class remained unmarried. But during this time in England a religous life was not generally considered a viable option for unmarried daughters and they remained within the family. The normative life pattern for well-born 15th century English girls was to be raised at home until adolescence and then be placed in another similarly-positioned household to learn adult skills, expand social networks, and enhance their marriage prospects. Depending on the relative status of the families, the girls might be treated as quasi-daughters or might be treated more as servants, but they would generally be part of a group of girls (and boys) of similar age and background who developed social bonds that would have consequences for the rest of their lives.

Women of this class and era might marry young and therefore not be sent away in this fashion, but more often would marry in their twenties or later, either while serving in another household or after returning to their household of birth for a time. Unmarried daughters were generally provided for in some fashion, sometimes sufficiently to establish an independent household, and there was an acknowledgement that a woman might “be not disposed to marry.” But generally they remained living with their families and contributed to the household administration and duties.

Given this context, it is a strong likelihood that Elizabeth and Agnes were friends from childhood, given the proximity of the two families and their relative status. They might have met while both serving in a third household, or it’s possible that Elizabeth remained at home and Agnes was placed with the more established and prestigious Etchinghams. Beyond that, several possible scenarios can be proposed. If Elizabeth fell in the younger generation (and thus died young), Agnes may have served as her nurse--which would have to have been an unusual bond to have been commemorated in this fashion thirty years later. In the scenario where Elizabeth was older, they most likely would have met and began their friendship during the adolescent outplacement of either both of them or of Agnes with the Etchinghams.

How did they end up both buried at Etchingham church? This would be the natural location for Elizabeth Etchingham’s grave. But the expected place for an unmarried Oxenbridge daughter to be married would be their family church at Brede, where her parents and siblings were buried. One possibility would be that Agnes lived at Etchingham after Elizabeth’s death and was therefore buried locally, though the two churches are not so far separated (12 miles) to make that a requirement. But almost certainly the burial location was due to a strongly expressed preference on the part of Agnes--not only to be buried in Etchingham but to be buried specifically next to Elizabeth. And the commissioning and placement of their joint memorial brass almost certainly would have been specified by Agnes in her will (which doesn’t survive) as no other explanation would make sense of this unusual event. It was extremely common for wills at this time to specify not only the church of burial but the specific placement of the grave next to other named individuals. Again, it is not unusual to wills to specify the imagery and text for an individual’s memorial, particularly in regard to soliciting prayers for God’s mercy. While this is the only currently known funeral brass commemorating two women, there are several other known medieval English joint burials of “unrelated” women or records of wills specifying such joint burial.

Bennett gives the background on the London workshop that produced this brass (and many others), including shifts in stylistic features that provide context for interpreting the image, as well as the general dynamics of memorial brasses. Much of the imagery was conventional, but within that there was a range of symbolism in the placement and nature of the figures. At this time there was a shift from showing the human figures face-on (in imitation of sculptural effigies), to turning them in profile, and especially showing couples facing each other, or with the wife turned more toward the husband. Elizabeth and Agnes are shown in complete profile, not only facing each other, but with their gaze meeting. Among various possible positions for the figures, this choice aligns with depictions of familial intimacy and physical closeness. Other possible design options at the time included the older front-facing style, or showing a lower status figure turned more toward a higher-status front-facing one, or with a devotional object placed between them to be the focus of a profile gaze. (There is a great deal of discussion of the specific nuances of this composition from among the range of known examples.)

For married couples, typically the man was placed at the viewer’s left in the higher-status location. Elizabeth Etchingham occupies this position in the joint memorial, possibly due to the higher status of her family and the location of the tomb on their property? The relative size of the figures also needs interpretation. Age is one factor represented by relative size, and the smaller figure of Elizabeth may represent her younger age at death, rather than specifically a difference in ages when they were both living.

Even given the presumption that Agnes may have specifically requested the joint memorial brass in her will, the approval and execution of the design would have fallen to her surviving relatives and the brass workshop. This means that the idea of commemorating the women’s close relationship was something considered unremarkable and desirable by their family circle. Interestingly, generations of historians describing the piece have gone to some lengths to avoid recognizing it as a commemoration of a relationship between two adult women, either describing it as depicting “two children” or mistakenly claiming that it was two separate brasses, positioned coincidentally, or even going so far as to claim that one of the figures was male! (An example is given of a different 14th century brass that clearly shows two men in calf-length garments and both wearing swords that a historian has labeled “civilian and wife”.) None of these earlier interpretations stands up to scrutiny. That said, while the memorial clearly commemorates a strong emotional and social bond between the two women, we can’t know for certain what the nature of that bond was beyond that. But the surface form of the memorial indicates that their families honored that relationship as being worthy of equivalent respect as that given to marriage.

Time period:

Place:

Event / person:

Sunday, November 12, 2017 - 10:00

Spring Flowering by Farah Mendlesohn is a gentle, domestic Regency romance, more in the vein of Jane Austen with its parson’s daughters and the family dynamics of middle class families “in trade”, than in the vein of Georgette Heyer’s dashing aristocrats and gothic perils. Ann Gray’s life is disrupted by the death of her father, the village parson, and she joins the bustling household of her cousins in Birmingham where the family business manufacturing buttons, jewelry, and other small metal accessories becomes the framework of her new social life. Until her father’s illness and death, Ann’s life had been taken up by the responsibilities of ministering to the needs of her father’s parish. Her future is open and unsettled now, with only the formalities of mourning to give her a breathing space to consider the options. Her loved ones--both the Birmingham family and her beloved special friend Jane, who has recently married--expect her to jump at the impending offer of marriage from the young curate who has taken her father’s place. But Ann thinks she doesn’t feel as she ought toward a man with whom she would spend the rest of her life, and an offer of a very different nature has arisen from the handsome widow, Mrs. King, soon to be a business partner of her uncle.

Mendlesohn’s novel is a refreshingly different sort of lesbian romance, depicting the attitudes and mores of the times with a social historian’s eye. The characters are neither anachronistically modern in their self-awareness of sexuality, nor anachronistically tormented and angsty about it. The physicality of Ann’s romantic friendship with her friend Jane is portrayed as completely ordinary for her times, but just as ordinary is Jane’s expectation that Ann will share her joy in her marriage. Through Ann’s explorations of new ties in Birmingham, we see how women who longed for same-sex friendships to be primary in their lives communicated and negotiated those feelings without needing to challenge social rules, as well as how families all too aware of the gender imbalance in the wake of the Napoleonic wars could encourage and approve of “surplus women” creating their own domestic arrangements. There are several very tasteful but explicit sex scenes that are well integrated into the overall emotional and self-realization arcs.

Although romance (with a few surprises) is the culmination of this novel, it is not the dominant theme throughout. Spring Flowering is a quiet tale of families and everyday life in Regency England, sweeping the reader into a world both familiar and intriguingly different in its details. There are a very few places where those details seemed to bog down the already leisurely pacing with a touch of “researcher’s syndrome,” but never in a way that derailed the story, as long as you approach the book as the story of a life rather than as a genre romance.

If you’ve longed to read stories of women loving women in history with happy endings that ground their love and their happiness in the spirit of the times, then Spring Flowering will be a breath of fresh air and a hope for a new wave of lesbian historical fiction.

Major category:

ReviewsSaturday, November 11, 2017 - 12:21

Lesbian Historic Motif Podcast - Episode 27 (previously 16b) - Interview with Farah Mendlesohn

(Originally aired 2017/11/11 - listen here)

This month's author interview is with Hugo Award-winning academic writer of literary analysis Farah Mendlesohn, who is taking her first step into being a fiction author this month with her lesbian Regency romance Spring Flowering. We had a lovely discussion about the varying attitudes toward same-sex relationships in different eras and the challenges of writing historical fiction.

* * *

(Transcript commissioned from Jen Zink @Loopdilou who is available for professional podcast transcription work. I am working on adding transcripts of the existing interview shows.)

Heather Rose Jones: Today, the Lesbian Historic Motif Podcast is delighted to welcome author Farah Mendleson to the show. Farah, I’m so glad you could join us.

Farah Mendlesohn: Thank you. It’s fantastic, particularly as we’re doing this across the Atlantic.

H: Yes! I’m going to start off with a slightly different opening question than I usually ask authors. Farah, you’ve written a number of critical studies of science fiction and fantasy literature. You’ve even won a Hugo award for co-editing the Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. You’re currently working on a massive definitive study of the works of Robert Heinlein. So, why is your first novel a historical novel rather than a fantasy or science fiction?

F: Oh. Well, first of all, because I’ve never been any good at writing science fiction, which is what I would write if I could. I must say, here, I never intended to be a fiction writer. I may be the only person you ever interview who never wrote fiction as a child unless absolutely forced to. Did it once as an undergraduate because the alternative was a major theoretical essay that, of course, I had not understood one word of. I was teaching creative writing a few years ago and a colleague who shall be nameless turned ‘round and said I shouldn’t be teaching creative writing unless I’d written fiction.

H: Oh, wow.

F: I was a bit irritated, so I spent the next year learning to write fiction. One of the people I modeled myself on is a British Children’s writer called Geoffrey Trease because he always wrote 60,000-word books. Because I’m very much a structuralist, I could break them down, and I could see what he was doing. I used his work as a model and wrote several historical pieces because all my degrees are in history. I’m not a literature person at all. I have three degrees in history.

H: That was actually something that was going to come up later in the interview because it looked like all of your teaching work has been in Literature.

F: No, not at all. I started out in American Studies, moved into History when American Studies started to fold in the UK, which it did across the country. Then I got pulled into Cultural Studies and then somebody said, ‘We need somebody to teach horror! You know lots about science fiction!’ I have no idea what the connection is. I found myself being pulled into the publishing department because of my work on science fiction conventions and work with publishers. That’s how I ended up drifting, but I’ve hardly ever taught straight Literature.

H: What’s your specialty in History? Other than American Studies.

F: Well, I trained in 1930s American History. I have a passion for the English Civil War and my current critical book is a book about Children’s Literature written about the English Civil War, which is fascinating.

H: That’s pretty specialized.

F: Yeah, it really is riveting. There is almost nothing more exciting than the English Civil War for all sorts of reasons, not least because the rate of literacy was at an all time high and lots of people from sections of society you would not expect, either to have left documents or to be engaged in politics, left documents and were engaged in politics. I mean, how can you resist Brilliana Harley, who in one breath is telling her son to send home some socks so that she can re-knit them, and in the next is writing him about the arguments between Parliament and the King. This is amazing stuff! But the Regency, of course we all read Georgette Heyer.

H: Yes.

F: It’s just a part of growing up and the early 19th century got more and more interesting to me through reading a book by somebody called Jenny Uglow called In These Times. It’s about Britain during the years of the Napoleonic War. Stuff I had never quite understood about that period started to make a lot more sense, which is that Britain is under siege, it’s poor, it’s isolated, and it’s insular. Also, by the end of the war it’s got a man shortage. All the things I realized I was fascinated by is that Georgette Heyer starts writing about the Regency during the man-shortage in the 20s and 30s.

H: Oh, I hadn’t made that connection. Yeah!

F: What she’s replicating is the post-Waterloo situation. The two periods actually match quite neatly in terms of the romantic stresses of the period. That, I think, might be why the stories she tells work so well for her initial audience. That’s why you have quite a lot of characters in it that are older women who missed out because their generation died on the field of Waterloo. It’s a fascinating period and it’s one that a lot of people don’t really make enough of when they’re writing that period. They always tend to focus on London or the countryside, when it’s the period that the great cities, like Birmingham and Manchester and Leeds are rising up. I come from Birmingham and if you come from Birmingham, you tend to be a bit of a patriot. It’s a lot like Chicago. If you think of the atmosphere of Birmingham of being very similar to Chicago, that sense of being a second capital.

H: Uh huh. I was thinking that what you were saying about the types of stories that get written during a man shortage that, with the American Civil War, the same dynamic was part of what contributed to women’s relationships, the whole romantic friendship/Boston marriage era. Where women were making their own households because they were extra.

F: Ooo. This is total piece of trivia. One of the writers I’ve been looking at this week is an American writer called Marie Beulah Dix, I think I’ve got her name right. She is an American, Boston woman who wrote historical fiction, which is very good, two of which are set in the English Civil War, who had close relationships with her female publisher and another writer and never got married. One of her stories is about a girl dressing up as a boy to go off to the war, because this child desperately wants to be a boy. There’s a lovely line in it about, ‘Any sensible girl has always wanted to be a boy.’ (chuckling) Little red flags going off everywhere. I think she went to Radcliffe and I’d love to find out more about her. Obviously, a late 19th century lesbian writer.

H: Let’s move on specifically to your book. I think it has become apparent in our discussion that this is a Regency romance type. Let me read the cover blurb for Spring Flowering. I got the cover blurb to work from because, at the time we’re recording, the book hasn’t actually come out yet. Though it will be out, as I understand, by the time we air. Here’s the blurb, “Everything changes for Ann Gray when her father dies, and her closest friend Jane marries and moves away. Ann must give up the independence and purpose she found as mistress of her father's parsonage in the country and move to her uncle and aunt's new-style house in the growing city of Birmingham. The friendship of Ann's cousins - especially the mathematically inclined Louisa - is some compensation for freedoms curtailed. But soon Ann must consider two very different proposals, either of which will bring yet more change. Should she return to her village home as wife of the new parson Mr. Morden? Or become companion to the rather deliciously unsettling widow Mrs. King...?” Do you follow more Georgette Heyer or are you following Jane Austen? Is it more the modern Regency romance or…?

F: I don’t know. In some ways it’s not quite either, in that there are no grand happenings in this book. It’s a very straight-forward story in which Jane’s father dies and she goes to live with her family in Birmingham. She meets people and she starts to settle in and she starts to develop. It’s quite a domestic story, so in that sense probably closer to Jane Austen. But you can’t be Jane Austen because Jane Austen is writing for people who take for granted the world she’s writing about.

H: Yeah. Yes.

F: Very often it’s actually easy to misread. Just a little example. I had a PhD student who wrote about how Jane Austen’s work reflects the esteem in which the navy was held. Having read Jenny Uglow, I was able to say to her, ‘No, Jane Austen is writing about the esteem she wants the navy to be held in.’ The navy is actually looked down on in this period. Partially because it’s a vehicle for social mobility because it lets oiks become Admirals. Tut tut tut.

H: Yeah, that comes up in a number of places, I’ve noticed.

F: It does and she’s assuming lots of stuff that we can’t. Because I can’t assume, for example, that you know the city of Birmingham. I can’t assume that you know the button trade of Birmingham. Or, okay, so I had to set the book within a particular three years because if I didn’t there’s no theatre. Why is there no theatre? Because Birmingham is a Noncomformist city, I think the Unitarians are growing so fast… No, it’s the Methodists… They’re growing super-fast that they build three separate chapels on the same site over twenty years. The chapel part doesn’t stay big enough. I had to explain things like that, the fact that the Noncomformists are actually ok with things like music hall, because that’s just performance, but they aren’t okay with theatre because that’s pretending to be somebody else and that’s untruthful.

H: Yes, in the excerpt from the book that I saw on the website, it was clear that the nuances of the various religious movements were going to be key to some of the characters.

F: Yes, and that’s the kind of thing that a 19th century reader would take for granted, but I can’t just assume that a 21st century reader will know anything about. I didn’t actually include the Quakers even though it’s a group I know most about because 19th century Quakers don’t look anything like 17th or 20th century Quakers and getting into that, people wouldn’t believe me when I explained. They’re barely even pacifists in that period.

H: When you were writing this book, were you treating it sort of as an homage to the genre of literature or more as a historical project?

F: Actually, it was a challenge. A friend of mine, Jane Carnall(?), who I’ve known for many, many years, we were having a discussion about whether we thought you could write a lesbian Regency and she felt it couldn’t be done because you couldn’t get the hierarchies of the relationships right. I thought it could be as long as I stayed within certain conventions that were an issue in the period. There’s a very good book called, In the Georgian Household [note: Correct title is Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England] by Amanda Vickery.

H: I think I’ve got that book.

F: It talks about the degree to which industrialization left families very anxious about their daughters. A lot of the reason why some women stayed unmarried was because they didn’t get to meet men. If you look at the Victorians, they tend to marry cousins and friends of brothers, but they stay very much within the family because that way you can make sure your daughter is safe in a world that is increasingly full of strangers. I realized that I could meet some of Jane’s concerns if I moved Ann into a quite tight-knit context. All of Ann’s possible suitors are either relations or business partners, either of her father, the Parson, or of her uncle, Uncle Joshua. I wanted to make that work and that was part of the challenge that I set out to do. The other challenge was that I really wanted some sex. I didn’t want to write a coming out narrative, so this isn’t a coming out narrative. Not least because I don’t think the Georgian’s would have understood it that way. To start with, they were much more sexual beings than the Victorians. They were much more comfortable at talking about sex, they knew what underneath women’s skirts and men’s trouser flaps, because, well, 80% of the population is still rural in this period. They know what animals do.

H: Yeah, one of the things that I find interesting in talking to authors of lesbian historic fiction is how many of them don’t understand the cyclicity of sexuality and think that you go back to the Victorian era and everybody was uptight, and nobody had sex and it must have been like that all the way back in history.

F: But the Victorians had big families… (laughter)

H: Yes, I’m talking myths here.

F: You don’t get big families by not having sex! But I remember my father talking to me years ago when I very first told him about my sexuality, and he told me about the nice two ladies who lived next door and only had one bed. Everybody knew, but nobody talked about straight sex either. In some ways, the most tricky point for homosexuals has been when heterosexuals talk about sex publicly. When everybody’s not talking about it, it’s actually kind of easier. One of my aunts was known as a career girl, for example, and [can’t make out] she went out with her lady friends. I had no idea what it meant, but it was a perfectly acceptable term.

H: I still remember the point when my mother casually mentioned, while working on genealogy materials, that, ‘Oh, your grand-aunt so-and-so, she was a lesbian, you know.’ It’s like, ‘What, what, what, what?’ This one in the early part of the 20th century.

F: The question that most intrigues me is, how do you know they were having sex? Well, thanks to Marie Stopes, we know that quite a lot of straight couples weren’t either. As a definition of an emotional relationship, that’s just silly. But yes, there’s also this thing that sex may be fairly similar and not change much, although even then, different practices are acceptable at different points, and desirable at different points. But the way people come together, and bond, has often got much more to do with economics. One of the fascinating things, accounts, is of William of Orange and his wife, Mary, because there’s some suspicion that both of them were gay and that both of them had partners. There’s a fascinating book, now, let me get this right, they’re not authors I particularly go for… The author of Mapp and Lucia, his father was a bishop and was quite well known for the young men he hung out with, but his wife, and she had six kids, was very clearly a lesbian.

H: I think I have that book on my list to cover for my history blog.

F: It’s a wonderful book, it’s hilarious. But it is quite clear that in a world in which, for the Victorians, women aren’t supposed to very sexual, therefore what women are doing together can’t matter.

H: Right.

F: Now, the Georgians think otherwise. The Georgians think of women as predatory and their approach is different. But it’s perfectly plausible that their relatively homosocial world, for men and women to just be getting on with what they want to do, while coming together to produce children within the economic unit. Unless you find that utterly revolting, which some people do, but most people kind of got on with it and then…

H: Had their fun on the side.

F: Not necessarily even thinking of it that way, just thinking of it as an intimate friend with whom they kissed, petted, and patted.

H: Yeah. This is one thing that I find fascinating, looking at the researching of lesbian history and the writing of lesbian historical fiction, have the same problem that so many modern people are looking for an exact mirror in the past, instead of embracing the past for what it was.

F: Yes, and I think people have always made their lives and that at various points that has been interfered with, with whatever the current scare was which has been expressed in many different ways. I mean, some accusations of witchcraft were probably about sexual practices, but it’s hard to tell. What we cannot assume, though, is that people did not have close emotional and physical relationships because they probably did. But how they thought of them, that’s trickier. I gave to my two a more open and clear sexuality, in part because they’re Georgians, not Victorians, they’ve not grown up protected. They’ve grown up seeing animals do things. But also because I get really bored with coming out stories. Oh, and I get really bored with the one true love trope. I’m thinking of writing a sequel and it might get a little more complicated.

H: I agree with you on coming out stories. One of the reasons that I dug deep into starting my historic research project was because I wanted to write historic lesbian fiction and I didn’t want to write just a whole series of coming out stories. I wanted to know… what did they know? What community did they have?

F: And people do construct community. People know each other, people recognize each other. I said I’m thinking of a sequel and that will involve some of that construction of community.

H: Great, I’m looking forward to that. In addition to this sequel, are there any other projects of yours that you’d like to mention for the listeners?

F: I don’t think my other work would be remotely interesting to other people. Although, the book I haven’t finished is a book on the children’s historical writer Geoffrey Trease and I’ll be working on that later next year. If you’re interested in historical fiction, he’s fascinating because he starts writing in the 1930s, he’s a genuine communist fellow traveler, by which I mean he goes to all the meetings but doesn’t join. He writes some of the first, to use the American phrase, ‘co-ed’ historical fiction. From 1940, he always has a boy and a girl. He has an awful lot of cross-dressing girls. He tries to write feminist heroines from very, very early on before it’s a norm for male writers. That might interest people, but the romance work is definitely something I think I’m going to pursue. It was rather a shock when this got picked up. I should explain: I tend to blog when I’m writing, and I do it because people asking me questions about my writing keeps me going. This was actually a Nanowrimo project and, as I was blogging and got to the end of it, Fiona Pickles asked if she could read it and I said yes thinking nothing of it. The next thing I knew, I found myself with a contract offer, thinking, ‘What? But, but, but…!’ As anybody will tell you, I have been saying for twenty years, ‘Oh, I’m not a writer, it’s just that I have things to say and the only way I can do that is to write them down.’ I’ve now been told very firmly, I am not allowed to say that I’m not a writer anymore.

H: Uh huh. I assume the book will be available through all of the regular outlets, Amazon, etc.

F: Yeah. It’s a standard kindle book. I mean, if you want a description, I would say it’s nice, slushy, bedtime reading. It was never intended to be a super exciting thriller or anything like that. It was the kind of thing I would want to read at night in bed… with chocolate.

H: On the off-chance that our listeners find you utterly fascinating like I do and want to follow you online, do you have a blog, do you want to give out your twitter handle? Facebook?

F: I have my twitter handle which is @effjayem and I will also have a webpage going live probably this weekend. It’s already live, it just doesn’t have much on it. That’s my full name, which is, unfortunately, very difficult to spell, but if you put Farah Mendlesohn, I usually come up.

H: Yeah, I’ll put all of the links in the show-notes so that people can find you easily. Well, thank you again, Farah, for joining us on the Lesbian Historic Motif Podcast.

F: Thank you very much, it’s been a lot of fun.

Show Notes

A series of interviews with authors of historically-based fiction featuring queer women.

In this episode we talk about:

- I chat with Farah Mendlesohn about her brand new lesbian Regency romance Spring Flowering.

- How did a literary theorist specializing in fantasy and science fiction come to write historic romance?

- Why was the 17th century a great time to set fiction about women loving women?

- How does historical fiction writer Geoffrey Trease come into things?

- How Spring Flowering came out of a challenge and a NaNoWriMo project.

- Books mentioned

- Spring Flowering by Farah Mendlesohn

- In These Times: Living in Britain Through Napoleon's Wars, 1793-1815 by Jenny Uglow

- Beulah Marie Dix (she wrote historical fiction in the early 20th century and was known to have relationships with women)

- Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England by Amanda Vickery (mentioned as “In the Georgian Household”)

- A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion, and the Bensons in Victorian Britain by Simon Goldhill

Links to the Lesbian Historic Motif Project Online

- Website: http://alpennia.com/lhmp

- Blog: http://alpennia.com/blog

- RSS: http://alpennia.com/blog/feed/

- Twitter: @LesbianMotif

- Discord: Contact Heather for an invitation to the Alpennia/LHMP Discord server

- The Lesbian Historic Motif Project Patreon

Links to Heather Online

- Website: http://alpennia.com

- Email: Heather Rose Jones

- Twitter: @heatherosejones

- Facebook: Heather Rose Jones (author page)

Links to Farah Mendlesohn Online

- Website: Farah Mendlesohn

- Twitter: @effjayem

Major category:

LHMPFriday, November 10, 2017 - 07:00

A historic fantasy featuring an ensemble of fascinating female characters--the "daughters" (in various senses) of various classics horror fiction protagonists. This is the sort of book that often leaps to the top of my to-be-read list. I liked it...but I didn’t love it, which always makes me sad. So first: why did I like it? The premise is full of promise. Mary Jeckyll (daughter of the late doctor) finds information after her mother’s death that results in her taking responsibility for a young woman named Diana Hyde, evidently the daughter of her late father’s assistant who disappeared after being charged with murder (the assistant, not the daughter). They stumble into participating in Sherlock Holmes' investigation of the gruesome murder of a prostitute, and soon clues are turning up to a mysterious “Society of Alchemists” that appears to tie all sorts of threads together, including several other rather unusual women whose fathers were similarly connected to the Society. For anyone familiar with weird literature of the 19th century, picking up on the hints and clues will be a large part of the fun of this story.

The writing is solidly competent and the characters of the various women are distinct and colorful. What didn’t work for me quite as well was the structure of the plot, which feels a great deal like working through the collective origin stories of a band of superheroes without quite getting to the adventure they tackle together. Each character narrates her history to the others which, while, it fills in essential information for the reader, results in a very slow build-up. The need to fit these expository chapters in where they don’t disrupt the flow of the action (which is quite dense and break-neck) can lead to some strange pacing, such as when Justine Frankenstein tells the others her story in the aftermath of the dramatic climax. To be sure, there is a climax and a natural conclusion to the book, as well as a clear opening for a sequel. But this book feels like the set-up for that sequel rather than a stand-alone story.

The other narrative technique that didn’t entirely work for me--and I feel like this is a bit petty--is the meta-fiction of the story’s structure. One of the women is writing up the adventure, deliberately in the style of a penny-dreadful and told from the points of view of the various participants. This narrative is interrupted at regular intervals by commentary among the women, criticizing the wording, their portrayals, and arguing with the choices of the writer. The meta-fiction is that the lot of them are, in essence, hanging over the shoulder of the writer as she works and having their interjections and comments recorded in real time. But the feel of it, to me, was more like an MST3K running commentary--more oral than written--which kept throwing me out of the meta-fictional context. (That is, I might not have been bothered if the side comments felt more like something set down originally in writing than transcribed from audio.) To be fair, it’s an imaginative technique and has the dual functions of turning what might otherwise be a somewhat flat narration into a more lively time-disrupted sequence, and of introducing us to the personalities of the entire group of women long before they enter the storyline, which in some cases comes fairly late in the game.

So, as I said, liked it but didn’t love it, primarily for structural reasons in the writing. But if you're intrigued by the female viewpoint on the consequences of classic horror stories, this will be right up your alley.

Major category:

ReviewsThursday, November 9, 2017 - 07:56

It's a regular feature of my life as an author to feel like I have to justify and excuse the fact that I pay attention to what the world is saying about my books. You see, authors aren't supposed to pay attention to reviews--whether to what they say or simply to their existence. Authors aren't supposed to mention that what readers do to help spread the word about a book is important, because that puts undue pressure on readers. But it does matter and we do care. And to balance out my occasional pleas (both silent and out loud) for people to help spread the word, I like to share examples of when you, my readers, have made a difference.

Yesterday when I was doing my routine name/title search in Google to see if there were any new reviews or mentions of my books, I turned up something exciting. (I'm not going to apologize for doing regular searches like this. Often it's the only way I ever learn about great reviews, and when I get great reviews, I add those reviewers to my list of people to suggest for review copies in the future.) The Barnes and Noble book blog included Daughter of Mystery in a list of "50 Magical Romances to Read Right Now". I think it's the only f/f romance included in the list, based on a quick skim of the summaries. And I am quite certain that it was included because of one of those twitter crowd-sourced requests for books with a particular theme.(*) And that means, that it was you, dear readers, who brought it to the blogger's attention and saw that it was included.

I don't know if you can imagine how great it feels to see my work side by side on a list put out by a major bookstore chain with authors like Nora Roberts, Mary Robinette Kowal, K.J. Charles, Zoraida Córdova, and Ilona Andrews. And you did that. You did it by telling the world how much you love my books and finding opportunities to recommend them to other people. It matters. And I love you for it.

(*) I'm pretty confident that Daughter of Mystery was included based on recommendations rather than the blogger having read the book, because the summary turns Margerit Sovitre into "Lady Margerit" which is a peculiar error to make if you've read it.

Major category:

PromotionPublications:

Daughter of Mystery